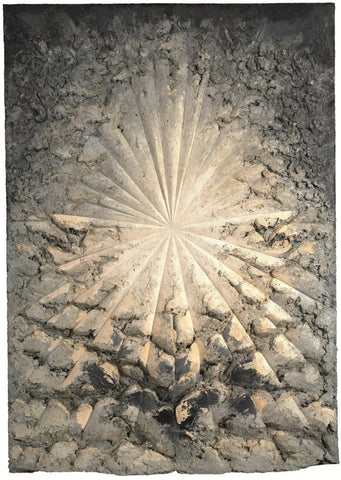

Jay DeFeo Working on The Rose

Jay in her Fillmore Street studio, 1960

There’s still some time yet to catch the Jay DeFeo show at the Whitney if you, like me, missed it at the SFMoMA. I had read about The Rose, but it was even heavier IRL.

There’s still some time yet to catch the Jay DeFeo show at the Whitney if you, like me, missed it at the SFMoMA. I had read about The Rose, but it was even heavier IRL.

Jay was, like, the hottest Beat chick on the San Francisco scene. She co-founded Six Gallery, which hosted Allen Ginsberg’s first reading of Howl in 1955, and was an original member of Bruce Conner’s Rat Bastard Protective Association. Her own work, combining unorthodox materials into hybrid sculptures/drawings/collages/paintings, positioned her among the vanguard of the Abstract Expressionists. Five of her paintings hung alongside groundbreaking work by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella in the important Sixteen Americans show at MoMA in 1959. She was on top!

One work that was requested for the MoMA show was a painting Jay had recently begun that was then called Deathrose. It was the concave, darker sister to another painting, The Jewel, that she began at the same time, working on “an idea that had a center to it.” Jay declined to include it in the show, but the MoMA curators knew that she was on to something and included a photo of it in an early stage in the exhibition catalogue.

Here’s Jay at work on The Jewel—

Jay DeFeo (1958) Photo by Jerry Burchard

Working on The Jewel at 2322 Fillmore Street, SF CA. 1959. Photos by Jerry Burchard

The Jewel, 1959

Jay took two years to reach a place with The Jewel that pleased her. Deathrose, which was later retitled The White Rose, and finally The Rose, took nearly eight years to complete, from 1958, when she was 29 years old, to 1966. She installed the canvas in a large Victorian bay window and worked up a tremendous surface of oil paint, carving it, adding mica chips, hacking at it, sometimes scraping it back altogether and starting again. There was broken glass in the window and no electricity in her studio, so both she and the painting were totally vulnerable to the damp. She worked by the daylight that steamed in from smaller side windows and against the tightening and loosening of the canvas that occurred as the seasons changed. (“Seasons” is hers. Isn’t it lovely?)

Photo by Burt Glinn, 1960

The painting went through many forms which Jay associated with the different cycles of art history from Primitive, to Classical, Baroque, and back to Classical. There is a wonderful collection of images documenting these changes on The Jay DeFeo Trust website, and here’s some I especially like:

Baroque phase, c. 1962-63

Toward the end, just prior to being removed from the studio in 1965.

Jay full on with The Rose, then a still from The White Rose, and a nice clear shot of the finished painting by Ben Blackwell.

Jay was made to call a truce with the already legendary painting in 1966 when a rent increase forced her from her studio. By then, The Rose had grown to nearly 12 feet high, up to eight inches think in places, and weighed over 2,300 POUNDS—far too large to fit out the studio door. It took sixteen guys a full day to cut out the window and some of the wall of the building, mount the painting to a larger canvas, and lower it down two stories with a forklift onto a flatbed truck. Bruce Connor documented this in The White Rose (1967), a film I’d like to see.

From San Francisco, the painting was transported to the Pasadena Museum of Art, and Jay went with it to keep working at it for another three months. When she really was done she dropped out to Marin and didn’t work at all for three years….

It was only after The Rose was briefly shown in 1969 at the Pasadena Art Museum, then traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMoMA) the same year, that she began painting again.

Jay with The Rose at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1969.

Unable to find a permanent museum home for her great work, The Rose ended up in a conference room at the San Francisco Art Institute. Conservators there estimated that it would take over 100 years for the thick oil paint to fully dry. In 1974 they applied a protective coating to the surface as that was intended as a temporary measure. The next stages of the planned conservation never happened, and in 1979 a false wall was built in front of the painting. There it remained, out of view, until 1995 when the Whitney Museum acquired it and took on the huge job of restoring it. By then Jay had been gone for six years.

It was all worth it.

Obviously there’s a lot more to this story. You can get started with the Smithsonian archive interview and with the Jay DeFeo Trust, but mostly make sure to see it if you can.

P.S. Jay on the left in 1986, photographed by Christopher Felver. Remind you of a certain hair hero, Wendo? Yeah, that’s “Lee” on the right with “Elliot” in Hannah and Her Sisters, also 1986.

Leave a comment